This version develops, elaborates on, and offers resources and examples for strategies summarized in the shorter , Don’t Just Sit There. Do Something (Short and to the Point Version).

Your camp is getting ready for their first field-trip to a swimming pool. Obviously, it is critical that they know how to behave safely. Before you line up for the bus, you need to go over some ground rules. You sit them down in a circle, emphasizing that it is very important that they pay attention. Within two minutes, Samantha and Lucinda are whispering to each other, and Devin is spinning around in circles. Within five minutes, Chloe is filing her nails, Lane is playing the drum on the floor with a pencil, and Carlton is doing everything in his power to crack-up Damon and Hwei Nyi. A few minutes later, you notice that D’Treena is staring out the window, while Antwan and Gavin are finger-kicking a paper football.

What is going on? You are not asking them to sit through a lecture on quantum physics. All you are asking of them is to listen to a few minutes of critical instructions. How will you respond? Yell? Deduct points from a reward system? Use time-out? Cancel the field trip? Ignore the behaviors and plow through the instructions anyway? Adjust your method of covering this essential information?

I am hoping you will consider the latter before resorting to any of the former strategies.

“But I am only asking them for a few minutes of their attention,” you are thinking. “What is so hard about paying attention for a few minutes?” Apparently a great deal.

In a study of children who were developing typically and children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Mark Rapport et al found that the ability of typically developing children to remain focused on-task was no more than 7 minutes, while the attention of children with ADHD ranged from 2 to 5 minutes, depending on whether they had been diagnosed with or without the attention deficit component of ADHD (Rapport, M. et al, 2009).

If you had asked the children to levitate in the air while listening to your directions, and they had not complied, do you think they could have done a better job if you had rewarded them? Punished them? Told them they were not trying hard enough?

Think about it. Sustaining attention is difficult for most people. When was the last time you sat through a drawn-out presentation or sermon, sat on hold, or watched someone explain how to operate a piece of equipment? How long were you able to focus? Whatever your capacity to focus, a child’s capacity is less. Whatever your capacity to PRETEND to focus, a child’s capacity is less.

In June, Deb Shapiro, my colleague from Camping for All, and I led a workshop on “Just Sit Time” for the summer camp staff of Charlottesville Parks and Recreation. Knowing that there were many years of experience and many outstanding camp leaders in the room, we decided the group could help us write this post. What follows is drawn from their observations and ideas as well as some additional observations and ideas offered by Ms. Shapiro and myself.

Danger Zones

We asked the 66 participants in our workshop to identify times that behavior tends to unravel.

l. These are there activities that they identified as most likely to be problematic:

- Waiting

- waiting for the bus.

- waiting to go into a site they are visiting on a field trip (for example, arriving at a pool that is not yet open).

- waiting for other children to finish an activity.

- Watching while one student does something (for example, a child and adult are in front of the group doing a science experiment while the other children are expected to watch).

- Listening to instructions.

- Transitioning from one activity to another.

- Large Group Times such as morning meeting, circle time, and lunch.

Keeping children’s attention focused during these times usually requires some level of support from adults. We asked our participants to consider how they might help their campers stay focused and appropriate during these particularly challenging times.

Great Expectations

- We‘ve got rules here. In their small group discussion, staff emphasized setting clear expectations, and I agree that this is extremely important. Expectations can be set up as rules at the beginning of the year, but they also sometimes need to be emergent and specific to particular circumstances. For example, I watched a site director explain to her camp exactly how they were to get up from their tables at lunch, with details about how to push the chair back. The latter she also demonstrated. Reviewing these expectations frequently during the first several days of a program can set a high standard.

- How would you rate that? A technique I have sometimes employed with success is asking children to evaluate themselves on how well they met expectations.

“You were expected to leave the cafeteria quietly and calmly, and we talked about how that would look and sound. If 1 was a great job, 2, a so so job, and 3 was a poor job, how well would you say you did?”

Accept their votes with no comment. I can only base this on my own anecdotal experience, but I found that my students’ self-awareness increased rapidly with this technique and that they quickly rose to the expectations.

- You tell me. In the example of leaving the lunchroom, the expectations were set by staff. Sometimes before beginning an activity, leaders may like to ask students, “What could go wrong here? Let’s list maybe five ideas for helping this activity go smoothly.” Following the activity, evaluate using the above procedure.

- I know what you mean. Just because you have tried to explain something doesn’t mean that your students or campers actually understand what you want. Using concrete examples can help increase understanding. “Listen to your counselor when she is talking,” is not especially concrete. Consider asking your campers how people look when they are listening (they are looking at the speaker, their bodies are still), how they sound (mostly quiet but sometimes they might murmur agreement or ask questions). Time invested in clarifying expectations will save you time spent explaining and disciplining later.

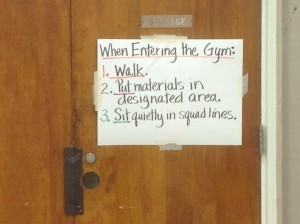

- Show me. Some children need visual cues. General rules, posted where everyone can see them, can help with this. But you may also want to write expectations for specific activities on

chart paper or dry erase boards. Images accompanying written rules , even simple stick figures, will help visual learners, struggling readers, and English Language Learners read and remember the written rules.

chart paper or dry erase boards. Images accompanying written rules , even simple stick figures, will help visual learners, struggling readers, and English Language Learners read and remember the written rules.

Describing and demonstrating. Using details. Writing things on a chart. Drawing pictures. Having students act out correct and incorrect behaviors. All these actions can help make expectations clear. Review and evaluate them frequently, especially at the beginning. And above all, make sure your expectations are reasonable.

Please. Let Me Explain.

Whether you are explaining your expectations, explaining directions, or explaining what is about to happen next, a certain amount of time is spent getting information across to your campers. I have watched groups devolve while leaders stood in front of them explaining and explaining. Invariably, the leaders become frustrated with the children as their behavior deteriorates. In some cases, I have seen them abandon the activity all together, because the kids “wouldn’t listen to the directions.” I totally get the adults’ frustration, but I don’t think the outcome was inevitable. It is possible to convey information without loosing your audience.

- For openers, be concise. In their time-honored book on writing and grammar, Skrunk and White encourage readers to “omit needless words.” As important as that advice may be to a writer, it is far more important to a speaker. You risk loosing your listener in a sea of language if you ask your campers to endure a verbose set of instructions.

How much verbiage could be cut here?

Okay guys, listen up. We are going to do an art activity now, and it’s going to be really fun, we’re going to paint the mural we sketched yesterday, but it’s important that you listen to the directions because if you don’t listen to the directions you will not know what we are going to do. I know yesterday, some of you were not listening before we played Capture the Flag, and you remember how confusing that was…right? So this time, pay attention when I explain. We are going to be painting the wall, and we don’t want the paints going all over everything and we are going to have a mess if everyone crowds the wall at once. And the last time we painted, when we did our self-portraits, no one cleaned up, did you? So, we are going to need to talk about this whole process, starting with selecting our paints. ‘Cause I know some of you are going to have certain paints you really want to use and others are going to want the same paints and I don’t want everyone to be arguing about what color they get to use first. You’ll all get the colors you want eventually,,,,,

and on and one and one she goes from picking colors to cleaning-up. Tell the truth: did you make it all the way through that speech? Imagine listening it it.

While the details are made-up in this example, the amount of extemporaneous verbiage unfortunately is not. How many children are still listening when she is finished? How many have stayed out of trouble? How many have been able to differentiate her main ideas in this tide of words rolling in?

Let’s try this again:

Okay guys, I need your attention for a minute. We are about ready to start painting our mural, but before we do, there a few directions and ground rules we are going to need to go over. Raise your hand if you have ever painted a mural before.

- Tempting as it is to explain why they need the directions, and what happened last time, this verbiage is adding “just-sit time” and probably confusing your students. Keep it concise and:

- Break it up. In the alternate passage, above, the speaker has not launched into a full explanation at once. She is going to break it down into small bites that her campers can digest. She is employing several other devises to keep her campers’ focus. She has opened with an

- Attention grabber. An attention grabber alerts the student that they really need to listen now. It can be perfectly straight forward, as in “I need your attention for a moment” or it can be intriguing. “Hey guys, did your parents ever tell you not to draw on the walls? Well, today you are going to draw on the walls.”

- Audience Involvement. After a very short introduction, the speaker has asked the students if they have ever painted a mural. By asking a question, she has engaged them, she has changed an expectation from listening to doing (raising hands if they have painted a mural), and she has made the information relevant by connecting it to prior experience. At this point, she should allow one or two students to comment, but not all, or again the rest will be lost in a sea of words, just not her words. She should also look for questions that will engage the students who have NOT painted a mural. (Have you seen a mural? Is a mural the same thing as graffiti?”)

- Let someone else talk. Look at the example paragraph above. How much of the information conveyed by the teacher could actually have been drawn out of the group? Not only does letting the students contribute engage them, it breaks up the monotony of listening to the same voice going on and on.

- Get silly. Another great way to grab and keep attention is to clown around just a bit. “We’re going to be painting a mural today, so I want everyone to crowd all around the wall and all of you try to paint the same thing at the same time, because that way you won’t just be painting the walls, you’ll be painting each other. Won’t Madison look good with a pink nose? No? Okay, well, how do you think we should go about this?” Don’t take this so far that you get your group wound up. A little humor goes a long way.

- Engage their eyes. Don’t just say it. Show it. Walk over to the paint table and pick up the paints as you talk about the colors they will be using.

- Engage their bodies. Likewise, get your students moving, even as you go through the instructions. “Okay, now everyone stand up, spread out a little, and pretend to paint on a mural. How far apart is everyone? Good.” Not only are you teaching to the active learners, you are keeping everyone’s attention by keeping them moving and changing things up. Do you want them moving because you invited them to move or because the fidgets have set in?

- Save some for later. Maybe you don’t have to explain it all at once. Can you begin an activity and stop after 10 minutes to explain the next step? Let’s say you are introducing a new, and rather complicated game. Consider breaking the game into segments the first time, then when the children have mastered the instructions for each component of the game, let them play it all the way through. You should tell them from the onset that they will have a chance to play it all the way through, but it is complicated so you are going to break it into three parts first.

- Repeat after me. Asking students to repeat back instructions helps you check for understanding and gives them a chance to talk (and hear a different voice). It also alerts them to the fact that they need to listen, because they are going to be asked to repeat your instructions.

Keep it in sight.

- Divide and conquer. How you group students plays into managing their behavior during challenging times. Whether it’s sitting in group time or waiting in line, you want to keep apart children who trigger one another’s challenging behaviors. If Carlton and Hwei Nyi wind each other up, move one to the back of the line and one to the front. If Samantha has been known to antagonize Shelby to the snapping point, why would they be seated at the same table?

- Get in there! Effective classroom teachers don’t stand in front of a classroom talking, they move about. Why should it be any different in an afterschool or summer program? The setting may be different. Maybe your group is on a golf course, maybe they are at various stations in a wildlife center, but you can still mingle. In a large group situation, walk through the group, making frequent eye contact and patting the occasional shoulder. Where groups are scattered around the setting, move from group to group. Spread your staff among your students. The very presence of an adult nearby can have a settling effect. If you know certain students’ behaviors can be particularly challenging, you want to make sure that those students are near an adult or that you are circling back to them often. But please, don’t do this in an obvious way that flags them as troublemakers.

- Case the joint. Physical environment has a powerful influence on behavior. You can allow the environment to work against you, or manipulate it to work for you. Look around the environment of your program. What blocks your view of a section of the space? A bookshelf, a hedge? Can the items be moved? Trimmed back? Is it possible that by standing in a slightly different spot you can see more kids?

If you are visiting a site, give the place a quick once over. Your students are standing in line for a ride an amusement park. One section of the queue runs behind a broad post: a great place for behaviors to devolve. Try stationing a staff member there, or make it a point to stroll over to that area often.

Find something to do. There are many opportunities for students and campers to find themselves with too much time on their hands. Maybe they are waiting for a bus that is delayed. Maybe one or two students are always the first to finish an activity, and their behavior begins to decay as they wait for the rest of the group to catch up. Be prepared to keep students occupied during these periods of otherwise unstructured time.

- Have a game plan. When the whole group is unoccupied, games can be played on the spot with little or no equipment. Keep a small juggling ball or scarf on hand and use it for a game of catch. Play charades and guessing games. Circle games are great. Younger kids may enjoy games like “Duck Duck, Goose”, while older students will enjoy more complex games, such as “Human Knot.” For this and other appropriate activities, see http://www.ultimatecampresource.com/site/camp-activity/human-knot.html and Making Fun Out of Nothing at All, Burcher and Burcher (available through ACA Bookstore: https://www.acabookstore.org/p-5625-making-fun-out-of-nothing-at-all-101-great-games-that-need-no-props-second-edition.aspx).

- A bag of tricks. In Enrichment Alliance programs, we have found it extremely helpful to keep a set of simple but engaging materials with us when traveling by car or bus. When behavior in the car was deteriorating severely, one of our drivers began traveling with a set of colorful pipe-cleaners in her car, which her passengers shaped into flowers and butterflies. Behavioral problems ceased entirely. One spring our students made lanyards while waiting for and riding on the bus. Decks of cards, games, books, finger-puppets, simple art supplies — these things can be thrown in a fanny-pack or day-pack and carried along on any trip away from site. Make sure items are not messy and do not have a lot of components. Also make sure they are cheap and expendable; they may get left on the bus. Maintain interest by changing things up from time to time.

- Up to More Tricks. At your permanent site, a box or shelf of tricks can be just as helpful. These can be made available for the inevitable students and campers who get ahead of the group. Keep high interest materials in a box that you can bring to a child’s seat, or direct the child to a well-stocked shelf. Getting back to expectations above, your students should already know what to do when finished early. A child milling around looking for something to do is a potential problem, but this is a situation that is easily avoided in a well-prepared environment.

- Can You Lend Me a Hand? Remember the study sited above which found that children with ADHD often cannot attend to a task longer than two minutes. Imagine what happens to a child challenged at this level when asked to sit at a table while materials are being passed out. To many adults who work with children regularly the solution is obvious: let these children be the ones who are passing the materials out. Look for other situations or times of day that certain children tend to become restless and assign them chores suited to their high level of energy.

- There’s Something in This for Everyone. The best science programs I have seen do not have one child up in front doing an activity while the other children watch; they have multiple stations in which children, who understand expectations for cooperative learning, complete the assigned activity in small groups. This should hold true for other activities, such as cooking. You can have multiple groups doing the same thing (everyone is constructing a simple electrical circuit) or stations with specific tasks (chopping, measuring, blending). It is not active learning if one or two students are active while the rest watch!

Change is Hard. During our workshop, staff identified transition times as among the most difficult times of their programs. There are numerous reasons for this, so I want to devote space to this topic, reviewing the ideas already discussed above as well as introducing some additional strategies. First, let’s consider all the reason transitions are so hard.

- Children may not want to quit the activity they are currently engaged in.

- The time and space covered in the shift from one activity to the next may lack structure and focus.

- Moving from one set of demands to the next requires a mental shift that is harder for some children than others, especially children with neurological challenges. A child who is in the mindset of playing soccer may find it exceedingly difficult to move into the mindset of cleaning-up the playground, even though this is an automatic transition for the majority of the group.

Behavior problems may arise out of the various challenges that transitions produce. Leaders who understand and anticipate these challenges can stay ahead of the game. We have already talked about several strategies than will be helpful here:

- Set and review clear expectations.

- Look for ways to keep students occupied physically and mentally during the transition.

- Mix adults throughout the crowd.

- Strategically arrange children who have difficulty with transitions close to adults and far from their most distracting peers.

There are additional strategies that can be particularly helpful with transitions.

- Advance warning systems. Transitions are hard. Abrupt transitions are very hard. Actually, children are no different than adults in this regard. Anyone will respond with frustration, inwardly or outwardly, on being commanded to stop one activity and shift abruptly to another, especially if the former is a preferred activity. Giving five minute warnings before ending an activity can prepare your children mentally and physically for the coming change. A verbal reminder may be enough, but for visual learners, I like to hold up five fingers. Various types of timers can be used as added visual cues.

- Rites of Passage. I know a camp that has an intriguing system of getting their campers into the dining hall smoothly. When the campers enter the building, they raise their arms over their heads and begin to chant “Ohhhhhhhhhhh….” as they take their places around their tables. Once the entire camp is gathered in the dining hall, they burst into an extremely lively rendition of The Johnny Appleseed Blessing complete with stamping and dosidos. With their hands and voices fully engaged while the dining hall filled, no one has had the opportunity to be disruptive, but the whole experience feels playful, not regimented like many other camp transitions I have observed. Moreover, this beloved ritual clearly signals a transition to a new activity, and the raucous singing shakes out the fidgets before the group settles down to eat. In other settings I have seen leaders use singing as a way to physically move from one place to another. Often these leaders will also look for ways to keep hands appropriately engaged. I know one who tells her group a different thing to do with their hands each day, such as making elephant trunks and tails.

- Be Prepared. Quick, efficient transitions are bound to go better than slow, confusing ones. Unfortunately, I have seen teachers delay an activity and drastically reduce adult supervision as they hustle from room to room gathering materials for the next activity. Needless to say, the situation in the room rapidly deteriorates. To the extent that you possibly can, prepare and collect your materials in advance. And as you set out materials, engage your students in this task as much as possible, especially those easily distracted children we discussed above.

From Danger Zones to Safe Zones

Failure to adapt activities to a child’s predictably short attention span has potential to result in disruptive behavior. This is true for all children, but more so for children with unusually short attention spans. Fortunately, there are many strategies that be employed to turn those “dangerous zones” into “safe zones.” Define expectations clearly, and review them often. Develop strategies that reduce the amount of time children are expected to sit doing nothing at all but listen, watch, and/or wait. Mix adults in with children. Prepare for transitions.

What are some of your favorite strategies for turning danger zones into safe zones? Please reply to share your success stories.

____________________________________________________________

Rapport, M. et al (2009). Variability of Attention Process in ADHD: Observations in the Classroom. Journal of Attention Deficit Disorders, 12. 563-573.