Please! Can’t You Just Sit Still and Pay Attention?

Mary Anna Dunn, Ed.D.

Originally posted on blogger.com., October 2012.

Among the concerns I have heard raised by enrichment providers, problems with distractibility and impulsiveness are certainly among the most common. Though it may be tempting to assume children with these issues all have ADHD, not every child who has issues with distractibility and impulse control has ADHD. Some are simply on the high end of active for any number of possible reasons.

Given that the relationship between the enrichment provider and the child is often very short term, it may not be necessary to know whether or not the child has ADHD or is struggling because of other, possibly temporary issues (such as adjusting to the unfamiliar environment of your program). What is important is this: if a child’s distractibility or impulse control challenges are interfering with her own or her peers’ opportunities to thrive in your program, she needs your help.

Keep in mind that you are not going to “fix” this child. You are not going to eliminate all problems that come up due to his challenges. But there are modifications and accommodations that may significantly improve his chances of having a positive experience in your program.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Look these tips over and pick and choose from the suggestions that work best for each individual. Remember that the child’s parents or guardians are among the best resources you can have for understanding how to support their child. Ask them for suggestions. I will write about communicating with families in a subsequent blog.

TIPS FOR SUPPORTING IMPULSIVE AND DISTRACTIBLE CHILDREN

A note on gender: in order to avoid the awkwardness of “his or her,” I will alternate gender between sections.

In order to protect the privacy of students, examples are composites or fictionalizations inspired by actual incidents, but significantly altered.

1. Spend some time focusing not on the child’s challenges, but on her gifts. Often the very behaviors that are driving you crazy are also a window into her delightful mind.

Once, I was asked to observe a six year-old in a before-school program who was having difficulty due to her distractibility and impulsiveness. When I arrived, the children were finishing breakfast. Within a few minutes of my arrival, she, like the others at her table, was beginning to clean up. She and her peers were gathering up napkins, placing forks in bowls, closing cereal boxes, and making all the other normal preparations for putting their snacks away. But as the other children continued with this unremarkable daily chore, I saw a gleam in our girl’s eye. Soon, she was building a tower of her breakfast articles. As the construction project rose perilously, the entire table began to shout, “Look what Georgia is doing!” Her behavior was problematic, but this child was a budding engineer, asking just the types of questions we want children to ask: What happens if I do this? How can I make this better?

Distractibility and impulsiveness are challenges. Flexibility and spontaneity are opportunities. Identify the ways your student demonstrates the latter, and help her develop these wonderful gifts.

2. Pay attention to seating arrangements.

- For group work, I prefer a learning environment in which children are seated in a circle. There are many reasons for this. For the sake of brevity, I will focus on those that affect the distractible/impulsive child: It keeps him in your line of vision and you in his; it leaves no one in the back of the room, where attention may more easily wander; and it enables you to keep all distractible children near you, without seating them next to each other.

- Pay attention to how children are grouped. Separate children who tend to get each other off task.

- Make note of potential distractions close to your student. An open window, a hall door, a colorful bulletin board, a pet—these are all things that some children can tune out and others cannot. An intervention may be nothing more complicated than quietly shutting the hall door as another group passes by, or rearranging the room so that circle time does not occur next to the salt-water aquarium.

- For small group and individual activities, it is important to make sure that a child who needs to focus is not seated next to a loud group. Sometimes noise is a symptom of engaged, meaningful learning, especially during the creative types of activities that happen during out-of-school time. The hubbub that can signal an engaged group can also be a distraction, but simple steps can improve the distractible child’s ability to concentrate. Try some of these ideas: place a table in a corner, with a chair facing a relatively bare wall and let her work there; allow the child to work just outside of the main room, door open, in plain view; or if they must be in the same room, place stations that are potentially noisy, such as board games, across the room from quiet activities, such as drawing.

3. Use your environment to support the child’s regulation of attention and impulses.

- Consider providing soft, air-filled cushions to place on a child’s seat if he is inclined to rock his chair. Not only is this safer, it is less irritating than the constant clang of chair legs on the floor.

- Your goal needs to be to draw your student’s attention towards what you want her to attend to, and away from what you don’t want her to attend to. Teachers often do this by using brightly colored chalk or dry erase markers, sometimes changing colors to highlight key concepts.

- Conversely, it is nice to have an area of the room that is relatively free from distractions such as posters, mobiles, pets, dioramas, etc., where the student can go if he needs to focus (see above).

4. Make sure “just sit time” is of an appropriate length and your distractible/impulsive students are well-supported. It can be frustrating to witness what happens when well-meaning adults expect children to sit or stand quietly for inappropriate lenghts of time, either listening to instructions or waiting for something to happen. This “just sit time” provides ample opportunity for the mind and body to wander and the fidgets to set in. Keep in mind that an adult’s attention span is shorter than an adults. It may be as short as 7 minutes for a child who has a typical attention span, and 2 for a child with a short attention span. (Rapport, M. et all, 2009).

- Do your best to keep the amount of time you are talking and children are listening short. If possible, break instructions into small chunks. Not only does this take less time, it makes retention of information easier. As an example, if your group is about to learn a new ballgame, don’t keep them on the sidelines listening to the rules of the entire game. Give them one set of instructions, let them practice, then move on to the next set of instructions.

- As already described above, pay attention to where your distractible/impulsive child is placed during ‘‘just sit time.” If possible, seat an adult beside him.

- Use visual cues. Some people are just not auditory learners and are really going to struggle when instructions are presented verbally, yet that is often how they are presented, especially outside of the classroom. In addition to your spoken instructions, use written instructions and/or drawings. Simple stick figures are just fine; you don’t need to be an artist. Visual cues are important for two reasons: they provide a focal point and a child whose attention has wandered needs a visual cue to get his bearings again. Often out-of-school time activities do not take place in a regular classroom, so you may find it challenging to provide these visual cues. Consider having a small easel chart or dry erase board handy in non-classroom spaces. Or, if available, pass out written instructions as a reference for those who need them.

- Sometimes “just sit time” happens during transitions, for example, your group has finished archery and cannot go the pool yet. Be prepared to keep the children’s attention when they are waiting for the next thing to happen. Great classroom teachers have a stock of tricks, or “time sponges,” they use to soak up those minutes of down time such as telling or reading stories, playing word, rhythm or guessing games, or asking the children interesting questions about themselves. For examples of “time sponges” see http://www.teachercreated.com/blog/2009/03/sponge-activities/.

- Provide the child with a meaningful activity during “just sit time,” such as passing out paint brushes.

- Keep your activities varied and alternate the types of activities. Try especially to mix up activities that require quiet focusing with activities that engage the whole body.

5. Monitor your student closely, especially during times known to be problematic, such as transitions and “just sit time.” Notice symptoms of restlessness and use cues to redirect her.

- Get in there! I have seen programs in which 50-60 campers were seated in a circle with two counselors, while six other counselors watched from the side-lines. Dispersing those six additional counselors through the circle would have vastly increased the support available to the impulsive/distractible campers. If you don’t have that staff ratio, walk about the group. Someone needs to be in close proximity to the group. They will know you are paying attention, and you we be able to support them by subtly pulling them back if they show signs of distraction.

- Making eye contact is often enough.

- Consider saying her name if you cannot make eye contact, but be mindful that by doing so, you are drawing everyone’s attention to her struggle.

- Unless there are rules in your organization against it, a light touch on the arm or shoulder can be helpful.

- Develop one or two simple hand signals so that you can communicate privately with a child who is struggling. As examples, a finger to lips when she is talking out of turn, or a finger pointed down to remind her to sit.

- Some teachers use laminated charts with rules, sometimes pictorially expressed, and quietly point to the rule that has been transgressed.

- Quietly remove a distracting object, perhaps replacing it with a less annoying alternative. For example, if a child is banging a soda bottle on the table over and over again, remove the bottle and pass her a soft fidget ball (nothing that bounces!).

- Keep “fidgets” on-hand. In addition to soft cloth balls, we keep coiled key chains, socks filled with beans, and other inexpensive, quiet items. I have seen one of our staff members support a child simply by handing him her own wrist band to play with.

6. Keep your behavioral toolbox well-stocked with a variety of excellent tools. If you are running a short program, maybe an art class that meets for one hour a week for six weeks, you may not be interested in setting up more than a minimal set of guidelines, but an after-school program or summer day camp that meets every day for several hours over an extended period of time is going to need a strong management program. If you are in one of these programs, such as a public school after-school program or a private summer-long day camp, you probably already have a system in place. Strategies and philosophies vary and in many cases are established through system-wide policies over which the individual provider has little control. In the space below I will discuss a few behavioral strategies. Consider how these could work in your programs.

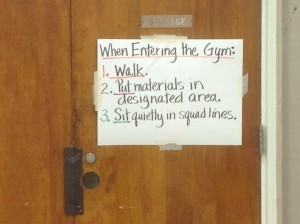

- Have a written set of rules visible in your primary workspace. Classroom teachers often develop these rules collaboratively with their students. Review the rules frequently and refer to them, or ask the child to refer to them himself when he is struggling.

- If you use a reward system, keep it simple and use it sparingly. Be aware that the use of rewards is highly controversial. I am a moderate on this topic. I believe that some difficult behaviors respond well to reward systems, but children who are rewarded throughout the day may become jaded by the rewards and, in addition, lose their sense of internal (or intrinsic) motivation. It is my own belief that rewards should only be used to target a small number of specific behaviors, and that rewards and the systems of delivering them should be changed occasionally. If reward systems are used, I like to see them incorporated into a multi-dimensioned approach to discipline that includes creating a supportive, positive climate and emphasizing internal motivation. Finally, I would urge program leaders who would like to implement reward or reward-punishment systems to do so thoughtfully, after thoroughly researching the most effective systems, rather than as a knee-jerk reaction. A poorly implemented reward system may potentially do more harm than good. [1]

- Take note of positive behaviors. If you are trying to help an impulsive or distractible child refocus, you may be spending a lot of time calling his attention (and often everyone else’s attention) to her negative behaviors. If all you ever notice is disruptive behavior, eventually the child and her peers are only going to think of her as a disruptive child. Please take the time to notice what she does well and provide her opportunities to do it in an appropriate setting. Remember the child who built a tower out of her breakfast items? While I sure don’t recommend reinforcing this experiment, it would be great to later-on make note of her building skills and provide her with construction materials. Make it a point to call the other children’s attention to her accomplishment (of course, you want to do this with the rest of the children as well).

- Do not take away active time as a punishment. Remember, these are children who need to move. Restricting their movements by keeping them in for recess or making them miss horseback-riding is not going to help them succeed. I am not saying I am opposed to imposing consequences—just not consequences that are going to make success even less likely.

7. Adapt your direct instruction methods. Even though this is not an academic setting, there will be instructional time. Children need to be told how to play golf, make a pizza, build a shelter, paint a mural, or participate in whatever activities your program is carrying out. I have already discussed incorporating visual cues. There are other ways you can make sure your instructional time is successful. The steps that make this easier for struggling students will surely be appreciated by the rest of your group, as they simply make your program more interesting and accessible to everyone.

- Introduce a topic by connecting it with something the children already know and have some interest in. For example, instead of starting a mask-making activity by talking about African ceremonial masks, ask the children when they have worn masks and why. Use their comments to segue into your explanation, referring back to their comments when possible. “Shawna said she wore a dog mask for Halloween. Well, African ceremonial masks are often animal masks, but they aren’t used for trick-or-treating. I wonder if anyone has an idea what they are for.”

- Don’t do all the talking. Give your students a chance to talk about what they know, as well as to raise questions.

- Break tasks down into small, manageable components and allow frequent breaks.

I hope that some of these hints will prove to be helpful in assisting the child who shows signs of distractibility and/or impulsiveness. At the same time, I would like to ask that the enrichment provider remember this: the fact that a child’s behavior is different does not necessarily mean it is a problem. Yesterday a staff member shared this story with me. He was assisting a child with special needs during a tennis lesson. The child was constantly in motion and seemed to be looking at anything BUT the instructor. His mentor did not think he was following the lesson. However, when the tennis instructor later asked him what he was supposed to do, the child was able to repeat back the precise instructions. Thank goodness the mentor waited to see if the child understood before he intervened. Not only was his activity not preventing him from learning, it is entirely possible it was a form of self-stimulation that was helping him attend. Some behaviors are problematic for others, even if they are not for the child, but often with a child who is really different than the pack, we, and not the child, are the ones who need some adjustments.

This discussion is far from exhaustive. I have tried to focus only on those strategies that will help in enrichment programs that take place outside of the regular school day. I have chosen a few websites that may provide more comprehensive discussions for those who wish to read more. While these sites do specifically focus on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, I wish to re-emphasize that not every highly active or impulsive child has ADHD. I do think that the strategies that are successful with these children are applicable to children whose challenges stem from other sources.

For further reading I suggest the following websites:

http://www.helpguide.org/mental/adhd_add_teaching_strategies.htm

http://www.drhallowell.com/add-adhd/adhd-for-teachers/

http://special-ism.com/creating-visuals-on-the-fly-for-unpredictable-activities/

http://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/CLC_RapportKofler2009.pdf

[1] The Tough Kid Book (2010) and The Tough Kid Toolbox (2009), by Rhode, Jenson, and Reavis, though arguably overzealous about reward systems, has some excellent strategies for changing rewards up and using them effectively.